Epiphany Chapel: A Revitalized Cross

Christopher Sanford Beck

Christopher Sanford Beck

So can you tell me about the story of the cross? We had the wooden cross—the plywood cross placeholder—and now we have your beautiful artwork. What was the vision to get from one to the other?

James Ceaser

I’ve been working here for a long time. I saw the original drawings for the chapel some 30 years ago, and I can recollect perfectly there was a stained-glass window in that hole. Every once in a while I mused upon the fact that they chose to board up the hole rather than put in a window. But it’s not my place, you know? I just work here. I’m just the maintenance guy.

I was hired in 1992. I had left engineering. I had gotten trained as a welder in order to have a more transportable skill that didn’t suck your soul to death, and so I could make artwork. But when I got out of welding school, there was no work. And so I came here, and they saw me as an engineer and wanted me to be in charge of the facilities. And after I’d been here a while, I thought, no, I really just want to make artwork, and so they hired somebody else to be the main person, and I just went around fixing things.

I was just the repair guy here. Right up until, I think it was when I made the Stations of the Cross at St. Mark’s College, which is a series of glass sculptures there. I also made a series of stained-glass windows for a church in Maple Ridge. That’s when I was kind of outed as an artist, and I was commissioned to do the imago—the big glass piece in the atrium.

James Caeser placing stained glass cross | Photo by Richard Topping

[Former Principal] Wendy asked me at one point to cover the plywood cross in the chapel, because that’s when we started doing more interfaith work, so they wanted to have a more multi-faith friendly environment. And so that is, in fact, when I started doing painting with, you know, seriousness. I did a bunch of paintings, and I actually talked to a bunch of different people, essentially asking, what would be offensive to you? Because I’m not going to do that. Whatever that is, right? And that worked out well.

So that painting that was hanging in Epiphany, then, you did that?

Well, it’s right here on the fourth floor. The actual original painting is by the alcove just up here. That’s the original painting. I got a high-res scan of it and printed it on massive fabric to hang in the chapel.

Wow, that’s awesome. I didn’t know that. I love the stained glass, absolutely, but I also sort of miss that painting. It’s really beautiful.

But back to the window. What is it about stained glass that either appealed to you when you first got into it, or that speaks to you now?

I had been building things forever, since I was a little kid. I had always been making things and making things that were quasi-artistic, but, certainly, there were no facilities or support for that notion of art. Even though I started working with glass, I was not thinking that way. I was not thinking that somehow this is art, or I’m an artist, or anything like that. I started making little hanging things that went in the window.

I had brought this little glass thing I had made to show the parish priest where I went to church, and he says, “You want to make a stained-glass window for the church?” I just sat there and stuttered. I said, “I guess so.”

Photo by Richard Topping

Then the priest at the other parish, you know, some miles away, heard about that window, and he says, “We’re building this new church here. Can you make some stained-glass windows for this?” And then, in the early 90s, I had been making glass things and glass windows for some time now. And I thought, Oh, you know what would be really cool is if I could do something like make them a little more three dimensional. So then I started doing figurative sculpture. Very shortly after that, I proposed a project for the chapel being built at St. Mark’s—this idea I had of making the Stations of the Cross in glass and as a cast.

I had been part of a sort of larger glass community here. And I got a scholarship to go to Pilchuck, the world Glass School in Washington State.

And since that time, I made a number of different sculptures and things, combining various media and stuff. In the last 10 to 15 years, I’ve most mostly been doing painting, oil on canvas. And one of the reasons I’ve done that is because you don’t get hurt as badly as when you’re doing sculpture, period. I mean, I’ve still got all 10 fingers!

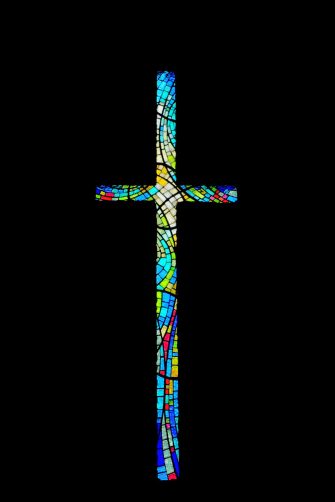

I’m curious about the window design itself—the colors, the lines. What was your inspiration behind the design?

Let me just say this up front, I had no clue how much light was going to be blowing through that thing. I was looking at just doing something very subtle, in blues and yellow and clear. That was my initial notion of it. And the people who commissioned it liked the design, but were like, “Can you put some red in it?”

So I set that first design aside. One of the things I’ll tell you about red is it blows everything out of the water. So I put red in it, but once you put red in, you’ve got to deal with red. I had to think, How am I going to make this an actual, proper, balanced, color form now that there’s brilliant red? And so that’s when a lot of other colors got introduced. There used to be three major manufacturers of this particular kind of glass. This glass is called dalle de verre, which is French for slab glass. It’s a 20th century thing. And it’s thick—it’s supposed to be three quarters to an inch and a quarter thick. Most of what’s in here is over an inch.

It’s less fashionable than it used to be. There’s not a church building boom going on and so stained glass period is not as big an industry as it once was. That shrunk and of course, dalle de verre has shrunk that much more because it was not the norm. When COVID hit, of the three manufacturers that were left in North America, two of them closed up. As far as I know, there’s really only two in the world. There’s one in Europe and there’s one in North America.

The moral of the story is, I had to make a bunch of compromises. I had the design—and then all of a sudden I can’t get half the colors, and the colors that I finally did get didn’t even match the one sample set that they gave me.

When you’re making something like this, what you end up with is what you end up with. Fortunately, red was a color I could get, I actually had some red from the stations of the cross. I still had glass left over and I literally begged, borrowed, and stole every color I could have.

So when it comes to the design, people have asked, “What is really going on there?” And my idea is that it’s twofold. There’s a lot of movement in it. I was determined to have no square lines. But also, I wanted to have an image that was—and this is the most important thing—that was continual behind the cross. There’s this greater reality that’s happening, and Christians are seeing it through the lens of the cross. It would be this dynamic, infinite reality that is going on back there, and you’re seeing it through your lens.

The moral of the story is, I had to make a bunch of compromises…

And I initially, in kind of a pedantic way, had intended to put the most light at the top. But then I thought, the light was from within, from the cross, the center. So that’s where the most light is let through. There’s much more light coming through that window than I thought there was going to be.

Were there any other unexpected things during the installation process, or is that kind of straightforward, once the design is all worked out?

Fortunately, I’m also a welder and an engineer, because it all had to be custom. All the installation bits were all custom, because the glass is really heavy. The whole cross weighs something like 300 pounds. All the panels have to be individually supported so it needed custom brackets built for all the pieces to go up. And the whole shape is irregular, which is why I needed the brilliant guys that were helping me. I asked them to take the cross out, the original wooden cross, and keep it intact, assemble it as one piece, and give me that to use as a template for the glass. Because it wasn’t square. Nothing was proper and I was having all these swoopy curves. The window is made in eight panels and each of the panels is curved on the edges. So it doesn’t look like it’s panels, it looks like they’re part of the design of the thing.

We were three days up there putting it in. And I had thought, Oh, well, one day tops. A long day, but it’ll be fine. Then, you know, it was three days. It was a lot of work: I was on the inside on a lift, and the workers were on the outside, high up, and we were lining everything up bit by bit by bit. It was challenging. But the guy who was helping me, Dylan, he’s a general contractor here who does a lot of work for us, and he’s a wonderful guy. He was so enthusiastic, and even now, he says this is the coolest thing he’s ever done—was putting this cross in.

It looks phenomenal. It really does. It brings the space to life in a new way.

It’s neat as an artist, but it’s also neat as just a guy who works here. I’ve done many things to change that space in very subtle ways over the last 30 years. But this is, like, this massive blast. Even more so than the banner. The banner was cool, but this is like, you know, heavenly angels.

Photo by Richard Topping

I can only imagine how much it must feel like that for you, with how much labor and love you put into that project. Because people walk into the chapel now and they have that angelic experience.

Thinking into the future, do you have any hopes for what this art piece, this project, might contribute to VST and the communities that are centered around Epiphany in the years to come?

You know, generally, I don’t even call myself an artist. I don’t mean that to be humble. It’s not like that. It’s like, I’m a guy who’s done some artwork and that makes a lot more sense to me. I’m making artwork. And I’ve been a lot of things and I’ve done a lot of things, but I think the cross lets some light in. It is automatically the focus in the chapel. Whereas it used to be the building and people would go, “Oh, this is a really nice building.” Now people walk in and they go, “Cross!” It’s unmistakable. It’s the first thing everyone looks at. And understandably so, and that’s great.

I’ve been here for 65% of the life of VST—something like that. So I have contributed a number of artworks here. This is, I think, probably the most visible one, and it feels good. It feels like it’s a legacy. I’m 61 and I’ve been here for 33 years. I’ve been here for over half my life and so this is kind of something to show for it. I mean, I’ve done other things in other places, but for whatever reason my world seems to have been tied to this place for a long time, and so it’s nice that I can leave behind something for people to, you know, remember me. It’s a gift. It’s a gift to give people.

It’s a gift that people are going to be appreciating for a long time to come.

I’m glad. Just don’t look too closely. I wish I’d done some things differently. You only know after the fact.

I’ve been here for 65% of the life of VST… so it’s nice that I can leave behind something for people to, you know, remember me. It’s a gift. It’s a gift to give people.

And now that’s part of the story too. That’s part of the piece. For better, for worse.

Thank you so much for telling me about the piece.

Thank you.

Now I want to go down to the chapel!

James Ceaser is a Vancouver-based mixed media sculptor, painter, and glass artist whose work explores the transitions between stages of existence through figurative work. With over three decades of experience, his creative journey includes studies at the University of British Columbia and the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design. In addition to his artistic practice, James is a Maintenance Supervisor at VST.

Interview edited for length and clarity.